In the wake of President Joe Biden’s disastrous performance in his June 2024 debate against Donald Trump, there was an avalanche of press commentary and backdoor gossip about the state of his reelection campaign. A drumbeat sounded again and again was the notion that, for the good of his party and the country, Biden should drop out of the race – that the danger posed by Trump was too great, that the polls indisputably pointed to voters not viewing Biden as a viable candidate, and that it was time for a new generation of Democrats to take the wheel. And almost from the start, many Democrats and journalists put forward one name to replace Biden: his vice president, Kamala Harris.

Harris, of course, would be next in line for the top job should anything cause Biden to lose the presidency before the end of his term. One must add to that Harris’ long experience in politics, from her work as a deputy district attorney at the local level in California to her term as a United States senator. Already the first woman, the first Black American, and the first Asian American to serve in the vice presidency, her candidacy and possible election would be historic, and a fresh success story for America’s melting pot ethos.

But the same long record that argued for Harris as a candidate has attracted intense criticism over the years. Her record on criminal law, her campaigns for various offices, and her handling of staff have all raised eyebrows and inspired doubts about her electability or effectiveness.

She dealt with discrimination from other parents growing up

Kamala Harris was born on October 20, 1964, in Oakland, California. Her father, Donald Harris, is an Afro-Jamaican American and a renowned economist and professor. Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, was a biomedical scientist who helped make great strides in the field of breast cancer research before her death in 2009. They met at the University of California’s Berkeley campus in 1962 and married a year later. Harris was the first of two children in the marriage.

Donald and Gopalan bonded over shared political beliefs; they introduced their daughters to the Civil Rights Movement when both were still in their infancy. But while Harris couldn’t recall her parents arguing much while she was growing up, their marriage gradually fell apart. They divorced when Harris was seven. Primary custody of the children was given to Gopalan, and Harris had only limited time with her father afterward. Donald has remained distant from Harris’ public life, and she rarely talks about him.

But it was during visits to her father in Palo Alto that Harris got a taste of the civil rights issue from another perspective. Palo Alto is in the San Francisco area, and a significant majority of its population identifies as liberal. But when Harris and her sister went out to play, the white children in their father’s neighborhood wouldn’t join in. “[They] were not allowed to play with us because we were Black,” Harris told the Los Angeles Times. “We’d say, ‘Why can’t we play together?’ ‘My parents — we can’t play with you.’ In Palo Alto. The home of Google.”

She grew up in a multicultural religious tradition

When it comes to religion, Kamala Harris identifies as a Baptist, and traces her connection to the church back to her childhood. While growing up, she had a downstairs neighbor who took Harris and her sister to the 23rd Avenue Church of God in Oakland, where the Harris girls lived with their mother. Harris has credited those early visits not just with helping her find her faith, but finding an early passion for public service. She specifically cited her exposure to the parable of the Good Samaritan as foundational to her future career.

But Christianity was not the only religious tradition Harris was reared in. Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, was a practicing Hindu; “Kamala” is another name for the Hindu goddess Lakshmi. As part of a broader effort to keep her daughters connected to their Indian heritage, Gopalan taught them the mythology of the religion and brought them to a Hindu temple in California. Gopalan also took her daughters on visits to India.

Due to the realities of American culture, Gopalan anticipated that her daughters would be primarily seen as Black, a reality Harris has acknowledged. But she has maintained some connections to her Indian heritage and to the Hindu faith. During her campaign for attorney general of California, Harris asked her aunt to break coconuts in a Hindu temple for good luck, a common practice in Hinduism on momentous occasions.

She spent her teenage years in Canada

Kamala Harris was born in California, and her life and political career is most closely tied to that state. But she spent a substantial part of her upbringing, not just outside the state, but outside the country. When Harris was 12, her mother relocated to Canada for work; she had a teaching job at McGill University in Montreal and a research job at Jewish General Hospital in the same city. She took her two daughters with her.

“The thought of moving away from sunny California in February, in the middle of the school year, to a French-speaking foreign city covered in 12 feet of snow was distressing, to say the least,” Harris wrote of the move in her memoir, “The Truths We Hold” (via the Press Republican). Compounding her discomfort was the language barrier. Partly to integrate her children in the language and culture of their new home, Harris’ mother enrolled her in a French primary school. Harris struggled with French, and her mother eventually transferred her to an English-language school. The timing was fortunate for Harris; laws passed in 1977 by the ruling Parti Québecois would likely have made it impossible for Harris to avoid attending French schools for the remainder of her education. She returned to the United States for college, attending Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Her early political appointments faced accusations of favoritism

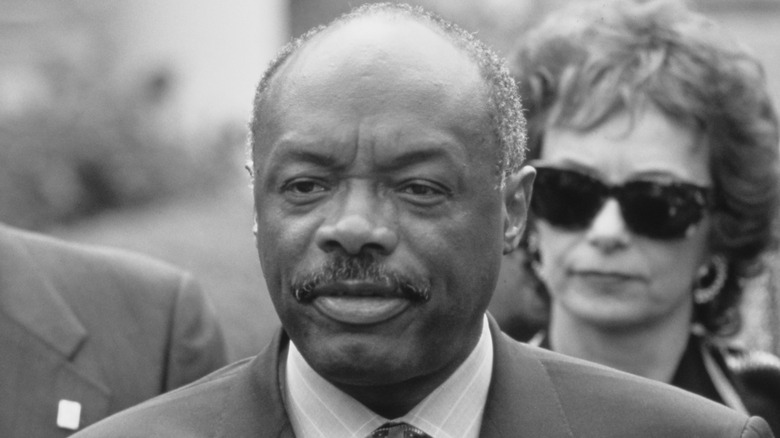

After her time at Howard University, Kamala Harris attended U.C. Hastings (now U.C. Law San Francisco), and graduated with a degree in law in 1989. She was soon working as a deputy district attorney in Alameda County in the San Francisco Bay Area. She also started dating Willie Brown (pictured), a prominent Democratic politician and attorney who would become the first Black speaker of the State Assembly in California.

Harris’ relationship with Brown would put a cloud over her early career in California politics. Brown faced considerable criticism during his time as speaker for awarding patronage jobs to friends and supporters, particularly during his final days in office. The positions he gave out tended to draw large salaries for relatively few hours. Brown appointed Harris to the the Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board and the California Medical Assistance Commission. The former position, which she filled for about six months, paid $97,000 per year, while the latter came with an annual salary of $72,000, reportedly for attending two meetings per month.

Harris has defended her role on both boards, maintaining that it was demanding work she took seriously. And she remained on the Medical Assistance Commission until 1998, well after her relationship with Brown ended. (They split in 1995, just as Brown became mayor of San Francisco.) But critics of Brown’s actions dubbed the appointments cronyism, and cited Harris alongside a handful of other names as suspect appointments designed to cushion vulnerable political allies or close associates of Brown.

Kamala Harris became San Francisco’s DA by running against her former boss

Whether or not her connections with Democratic bigwig Willie Brown helped Kamala Harris’ early career, she didn’t get into the San Francisco district attorney’s office by his doing. She was appointed to the office’s career criminal division in 1998 by then-District Attorney Terence Hallinan. Just five years later, Harris was running for the top job herself, in competition with the man who appointed her. And theirs was a bitter campaign, one that drew on insinuations about Harris’ relationship with Brown and the state of the D.A.’s office under Hallinan.

Harris only worked under Hallinan for two years. While the two shared an ideological outlook, particularly on the matter of prosecutions, Harris found the D.A.’s office under Hallinan to be overly political at the expense of efficiency. Some 52% of felony cases filed by Hallinan’s team were won in 2001, compared to the 83% state average. (Hallinan claimed his rate was 80% on violent crime.) She also accused his office of being tainted by corruption, a charge Hallinan and his supporters threw back at her by touting his record and insinuating that her connections to Brown would compromise her on the issue.

Harris and Hallinan made it to a runoff election in 2003. Harris raised more campaign funds than her opponent and effectively maneuvered behind the scenes to deny him an endorsement from San Francisco’s Democratic Central Committee. (The body endorsed no one.) In the end, Harris won with 56% of the vote.

Her record as California DA has hurt her with progressives

As a prosecutor and district attorney, Kamala Harris was part of a “tough on crime” wave that coursed through the Democratic party at the turn of the millennium. In her campaign against Terence Hallinan for San Francisco D.A., she opposed the death penalty and supported medical marijuana. When she was sworn in as California’s state attorney general in 2011, she said that prosecutors must have convictions as well as win them and that “we are going to need to get smart on crime — tougher and smarter — about making California the undisputed national leader in innovation in crime fighting” (via the State of California Department of Justice).

But as the state’s top prosecutor, Harris was responsible for enforcing the law as it was, not as she’d previously campaigned she’d like it to be. That meant enforcing the death penalty. Harris went further than that, appealing a federal court decision that branded capital punishment unconstitutional. As attorney general, Harris also supported keeping marijuana illegal until 2017 and tried to keep wrongfully convicted people in prison.

Against this, Harris and her supporters have pointed to more progressive aspects of her time as prosecutor, from her advocacy for drug-policy reforms to her cautious use of California’s “three strikes” law. But she retains a reputation among some progressive Democrats as overly aggressive as a prosecutor and disingenuous about her record. And her “tough on crime” attitude is considered out of step with the Democratic mainstream, which has increasingly advocated for criminal justice reform.

Kamala Harris brought California billions in environmental settlements

As district attorney of one of America’s most liberal states, Kamala Harris’ climate policy was bound to attract scrutiny in and out of office. While Republican politicians have been expectedly critical, climate is an issue where Harris has received high marks from her fellow Democrats. As the district attorney of San Francisco, she established the city’s environmental justice unit. And her record of pursuing action against high-profile environmental offenders as attorney general is an aggressive one.

Among Harris’ achievements in environmental justice was taking on Volkswagen, and not for their dodgy advertising. Over a six-year period, the company rigged assessments of their vehicles’ nitrous oxide emissions to read low when they were well in excess of legal levels. Harris’ office brought claims against Volkswagen and was able to obtain a settlement worth $14.7 billion, of which $86 million went to the state of California. Harris also secured settlements from Chevron and BP, joined a coalition of pro-environmental attorneys general in 2016, and sued the Southern California Gas Co. over the largest gas leak in U.S. history.

Harris continued to advocate for environmental causes as a senator and a presidential candidate. She and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez worked together on a climate equity bill in 2020.

She didn’t face a Republican during her Senate run

Kamala Harris launched her campaign for senator from California in 2016, hardly a quiet year in American politics. But in California, the race for a Senate seat was not one marked by a bitter contest between rivals in opposing parties, or even a sober and respectful debate between a Democrat and Republican. Harris ran without opposition from the opposing party.

This was a result of California’s top-two primary system, under which primary voters cast their ballots for any eligible candidate for Congress or state office regardless of their political affiliation. The system, established in 2010, had still seen Republicans make it onto the ballot even as their presence in California politics shrank. But in 2016, the Republicans vying for a Senate seat added up to a large field, most of them unknown and none of them able to rally enough support. It was the first time in California history that a Republican wouldn’t be on the ballot since senators became directly elected rather than appointed.

Harris won the primary. The second place finisher, Loretta Sanchez, became her opponent in the runoff. Having already secured the endorsement of the state party during the primary, Harris was the favorite to win the seat, and so she did. Harris took over 60% of the vote in 2016.

Her 2020 primary campaign has been widely criticized

Kamala Harris didn’t stay in the Senate for long. Before her first term was up, she entered the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, and was later chosen as vice president on the successful Democratic ticket. But as vice president, Harris has largely been kept off the front lines. And from the days of her primary campaign, she has faced questions and challenges to her ability and electability.

That Harris lost the race for Democratic presidential candidate is obvious. She began the primary with considerable media attention, particularly after she went on the attack against Joe Biden. But the early buzz around her proved unsustainable. Her inconsistencies on health care cost her with voters, and leaks about staff turmoil hit the press in the latter half of 2019. The picture painted by those leaks was one of a campaign considerably more divided than those of other candidates, with Harris oblivious to the infighting or incapable of controlling it.

Complaints that Harris’ was a volatile and ineffective staff continued when she entered the Biden administration. Others have suggested that Harris was chosen primarily to tick demographic boxes, and if it weren’t for them, her primary campaign and unpopularity with a plurality of voters would have disqualified her. Harris’ polling numbers sank to 28% by 2022, the lowest of any vice president in modern U.S. history.